Bringing Boredom Back

In today’s society, it is rare to see someone sitting idly. As a child, I remember visiting the local mall on Saturday mornings with my grandparents. We didn’t go shopping, but instead we went for a walk and looked around. My grandfather would often find a bench and simply sit, watching people go by. There was no phone in our hands, no earbuds in the ears, no screens filling the walls. It was just us and the steady rhythm of passersby.

Often, these quiet moments led to small conversations with strangers sitting nearby. Looking back now, as an adult fascinated by brain development, I wonder what was happening in my own brain during those moments. I was sitting, watching, listening and absorbing. Without realizing it, my brain was in what we now understand as its default mode.

Many of us born in the 1980s and 1990s can recall similar moments of unstructured time and “nothing to do.”

These moments of boredom felt ordinary when we were young, but why are they actually so important for a child’s developing brain?

This default mode network is activated when our brain turns inward, when we are not engaged in a specific task. It allows the brain to sort recent experiences and strengthen neural connections. This default mode can look like daydreaming, using our imaginations, meditating, and self-reflection. When you see a child engaged in these moments, they are, in a sense, filing information they have learned in more meaningful ways. Research has shown that our brains are actually more engaged when when we appear to be at “rest” (when the default mode network is activated), than when we are focused or engaged on a particular task (Buckner & DiNicola, 2019).

In today’s classrooms, it is very difficult to get children to relax into these states of boredom. Their brains are firing so rapidly and are not well-trained to shift into default mode. When the brain has no external stimulation, it must create its own, which takes patience and practice that feels unfamiliar in today’s fast-paced society. Once the process is established though, this activates creativity, independent thinking, and idea generation. This forms the mental foundation for problem-solving and innovation. Not only is this important for developing problem solving skills, but it is also essential for emotional regulation.

So how do we help children practice and embrace boredom?

Boredom comes with mild discomfort for all of us, especially at first. If we can help children sit with this discomfort, we can slowly build their endurance for boredom. The brain begins to learn that discomfort is temporary, tolerable, and can ultimately lead to rewarding experiences.

When the brain is in a state of constant stimulation, it remains stuck in a reactive mode. We need the prefrontal cortex to have opportunities to practice self-regulation. Over time, the stress response will no longer be constantly activated or waiting for the next thing to happen. These experiences gradually build patience, resilience, and frustration tolerance. Just as muscles need time to rest after a workout, our attention improves after periods of mental quiet.

The shift occurs when a child becomes intrinsically motivated. They must want to sit in these states of boredom. Perhaps children have not yet been made aware of the importance of boredom. Often, when we share what is happening inside their brains, they are motivated to make changes to improve their brain functioning.

When boredom lasts long enough, the brain begins to ask, “What do I want to do? What interests me right now?” Children start acting based on internal curiosity rather than external rewards or prompts.

During these moments, the brain connects ideas, processes emotions, builds creativity, strengthens self-regulation skills, and learns how to initiate action. Boredom is not empty space; it is mental construction time. What feels like passive thinking is actually the brain actively constructing meaning. It weaves information from many sources, including past events, future plans, and imagined scenarios.

The brain processes multiple cognitive functions simultaneously including self reflection, imagination, memory retrieval, and language related internal thought. Mental construction time, therefore, is a complex and coordinated set of brain activities that are neither random nor purposeless; it is essential.

In this “daydreaming” state, the brain is not quiet; it is in an active shifting mode that supports creative and original thinking.

How many problems have you solved while taking a shower? That is mental construction time at work.

Tips for Teachers and Parents:

Boredom doesn’t need to be forced, but it does need to be protected.

Build in intentional quiet time - allow time for no planned activities or directions.

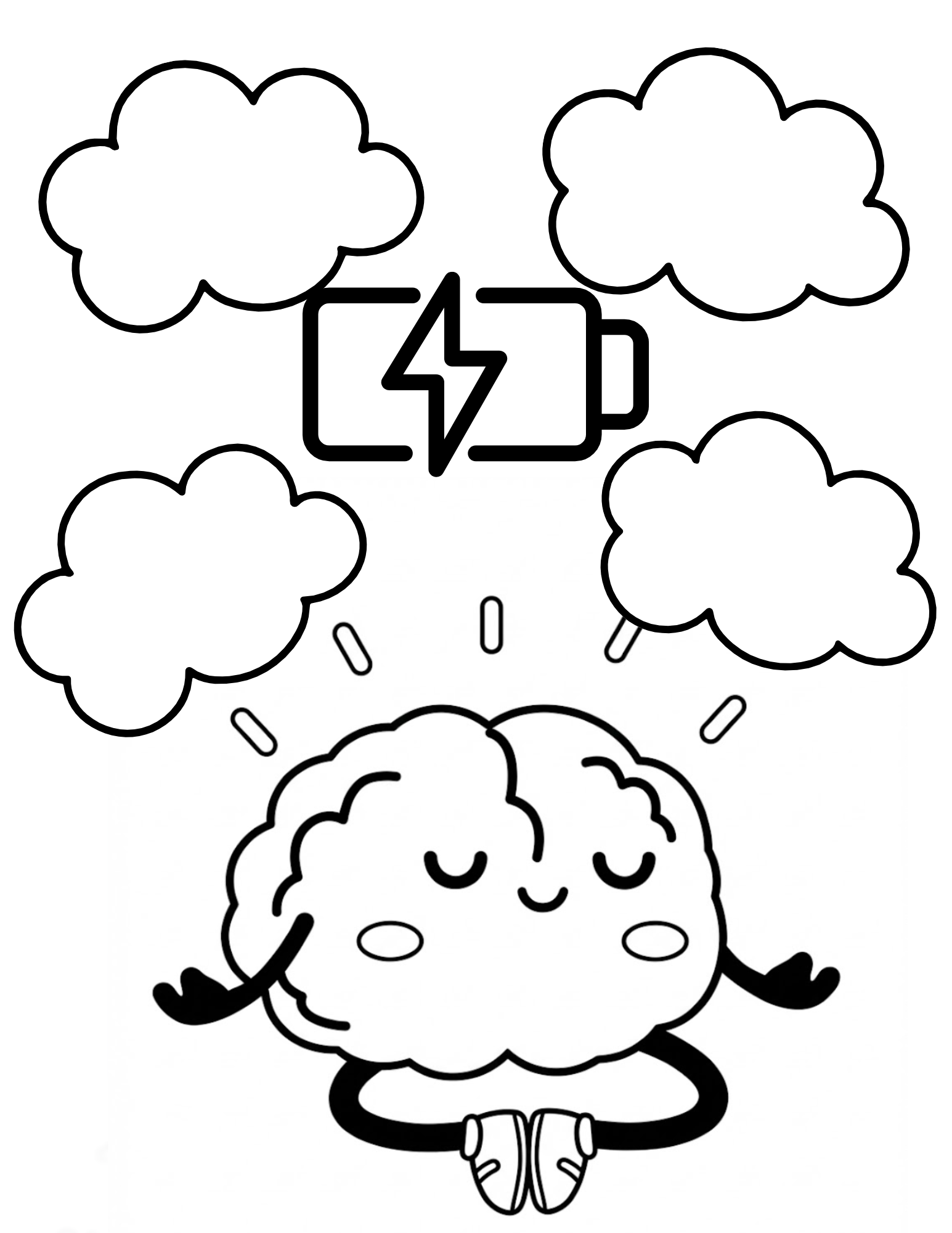

Introduce simple mindfulness of breathing techniques - get comfortable in stillness

Offer open ended creative materials - crayons, markers, paint, clay,

Encourage coloring without a goal - free coloring, no worries about staying in the lines- allow the brain to slow down and self direct.

Create space for building and constructing

Provide puzzle and brain teasers - allow them to work through mild frustration independently.

Normalize day dreaming moments - bring back staring out the window or up at the ceiling.

Limit immediate access to screens - screens eliminate boredom!

Use supportive language when children say, “I’m bored”: Respond with something like, “That’s ok. Your brain will think of something to do.”

Model boredom intolerance as adults - let them see you sitting quietly, reflecting, reading without constant phone use.

Never underestimate the power of a long shower or hot bath as a brain reset

Outdoor walks allow time for our brains to wander and connect to the world around you.

Create tech free zones - like the dinner table and bedrooms

Shift the narrative from deprivation “I can’t use my phone” to self-care “I’m taking care of my mind.” (see coloring page- in clouds write self care ideas you enjoy)

Instill a mantra as a family: Screens fill your time, boredom fuels your mind, Don’t drown the daydream, let your mind wander so it doesn’t get lost. (see coloring page)

Reset then connect - allow yourself screen time after spending time resetting. Set a timer for 10 minutes of scrolling at a time. Try to stick to 30-60 minutes of screen time a day.

View time away from screens (hyper arousal) as giving your brain a hug. Boredom lowers cortisol and allows the nervous system to regulate giving the brain a hug of chemical calm.

The framing is everything, if we say here are boring activities they will hate it - stress the importance of “hugging our brains”.

Create an “I’m Bored” activity jar: see printable ideas to put in the jar

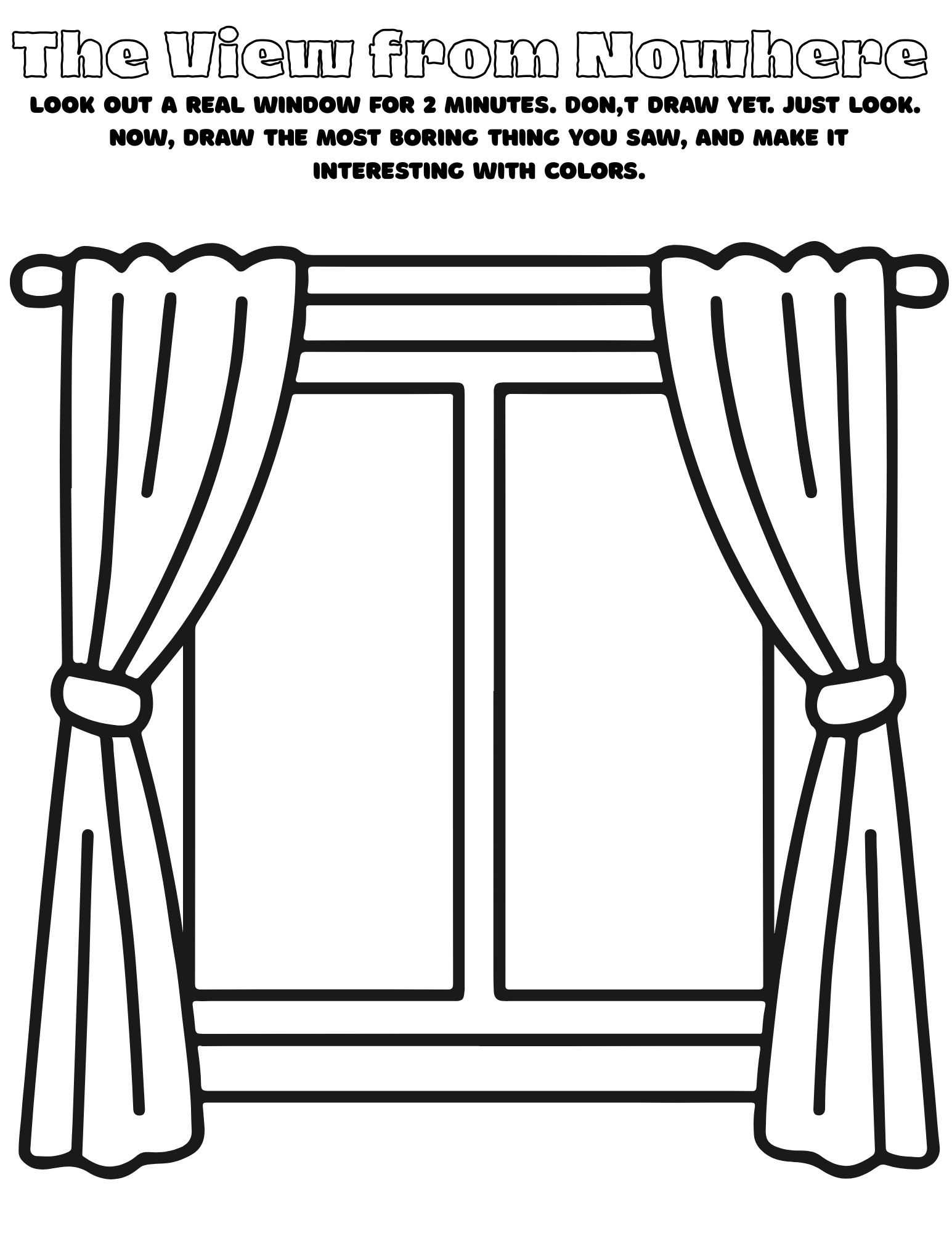

The View from Nowhere activity - see printable activity

The Squiggle Starter - see printable activity

Zentangle Art - see printable activity

Resources for Further Learning

Mind in the Making: The Seven Essential Life Skills Every Child Needs | Ellen Galinsky (Audible) (Paperback)

Rest Is Not Idleness: Implications of the Brain's Default Mode for Human Development and Education | Immordino-Yang, Christodoulou, & Singh | Perspectives on Psychological Science

The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent | Ginsburg | American Academy of Pediatrics

Why your Brain Needs More Downtime | Ferris Jabr | Scientific American

The Brain’s Default Network: Updated Anatomy, Physiology and Evolving Insights | Buckner & DiNicola | Nature Reviews Neuroscience