How Brain Science Transformed the Way I Teach

Like many teachers, when I entered the profession I thought I knew what it took to be a teacher. I spent 20 years of my life as a student, how hard would it be to step in front of the classroom? In reality, I knew little to nothing about teaching and learning even after completing a traditional teacher certification program. That program taught me important instructional skills including: writing objectives, lesson plans, unit plans, assessments, how to conduct action research and ways to create an equitable classroom. I also took a course on the psychology of learning, we learned about Piaget and a little anatomy of the brain. The piece that was glaringly absent from my teacher preparation program was how to use modern understandings of brain science to inform the decisions I make in my classroom day in and day out.

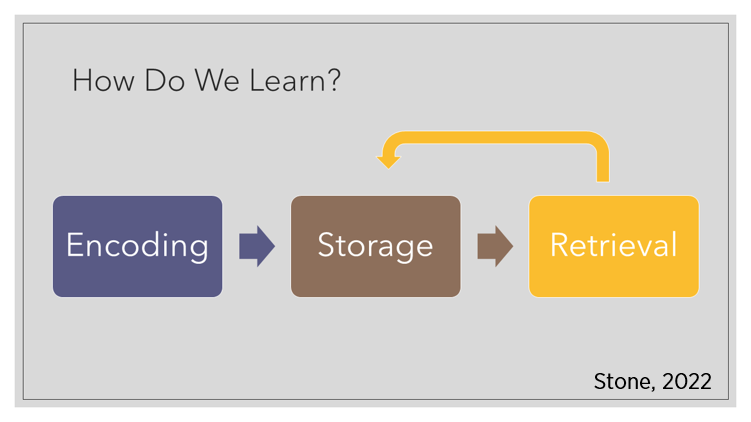

Cognitive science is the scientific study of how humans learn. This field originated in the early 1950s with the “information processing” model of learning (Smelser & Baltes, 2002). The information processing model tells us that the brain receives sensory information, some information is ignored, and the information the brain pays attention to becomes encoded into short-term or working memory. Depending on how distracting the learning environment is, student prior knowledge and working memory capacity, some or all of the information stored in working memory becomes incorporated into long-term memory. Once information is located in long-term memory, students are able to pull that information out from long-term memory back into working memory, which is known as retrieval. The more often we retrieve information, the stronger the neural synapses involved in these memory pathways become, and the less likely we will forget it over time.

At some point in my teaching career I’m sure I was taught this information. I am equally sure I was never taught how it directly relates to everyday teaching and learning. I taught for ten years before I started applying cognitive science to what I do in my classroom. My journey was prompted by a very challenging class of students. At the end of every day I felt like I had failed those students. I tried multiple interventions, I reached out to our district coach for help, but everything felt like bandaids. I knew my teaching practice could be more effective so I began searching for answers.

Making Retrieval a Central Practice

The summer following that challenging year I stumbled upon the Cult of Pedagogy Podcast. One episode, in particular, opened my mind to new possibilities: Episode 58: Six Powerful Learning Strategies You MUST Share with Students (Gonzalez et al., 2016). In this episode, cognitive scientists Yana Weinstein and Megan Smith (Sumeracki) explain how six strategies supported by cognitive science research can have a direct and positive impact on student learning. Two strategies, in particular, resonated with me: retrieval and spaced practice.

Upon reflection, I realized that I spent most of my class time trying to stuff information into the brains of students (encoding) but I spent much less time asking students to pull that information back out of their brains (retrieval). My students were passive in their learning and that didn’t make things stick.

I started looking closely at each lesson to see if I could figure out a way to flip flop and make retrieval central to my instruction. It dawned on me that what I was learning about learning needed to be shared with my students. For years, I struggled with students who performed poorly on assessments even though they were seemingly doing all of the assigned work. Now I had answers for them! When I asked students how they studied, the most common answers I heard were: “I re-read my notes”, “I rewrite my notes”, or “I don’t study.” I had to wonder about the students who said they didn’t study. Was it because studying never really worked because they were using the first two strategies, and gave up? I began explicitly teaching my students the science and practice behind “information processing.”

I started using the same language that cognitive scientists use with my students. I started by assigning practice in class. A student would inevitably ask, “Can we use our notes?”, and I would say, “No.” Then, I would ask the class, “Why don’t I want you to use your notes?” and they would chorus, “Retrieval!” Framing classwork this way, even though it was a small shift, drastically changed how my students approached classwork. Instead of school work feeling like something to complete and file away, students connected practice with the deeper mastery of key concepts and preparation for eventual assessments.

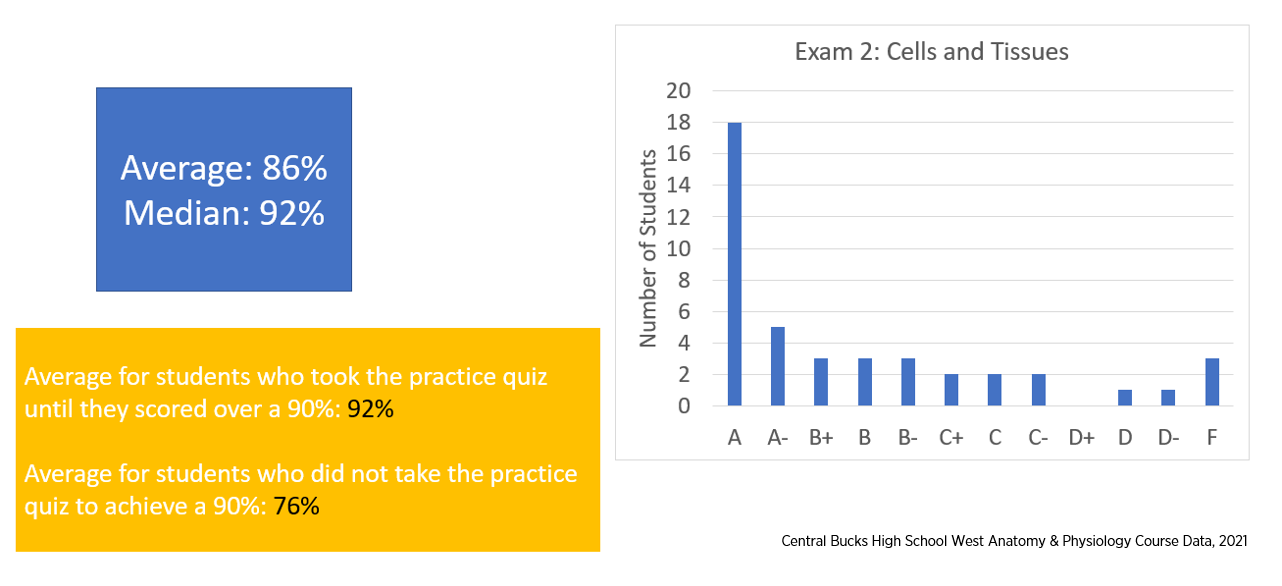

One other really key piece of implementing retrieval strategies in the classroom is to make sure that these activities are low stakes or no stakes. 99% of retrieval in my classroom is NOT graded. That doesn’t mean that I don’t keep track of scores or attempts but it does mean that students are not academically punished for poor grades on retrieval practice. The data I collect is primarily used to generate conversations with students about their progress.

Additionally, I changed how I approached homework. Instead of homework being “encoding work” (reading and taking notes) it is now retrieval and spaced practice. Spaced practice is when students retrieve information at regular prescribed intervals to prevent decay of long term memories. I assign short, no stakes, practice quizzes regularly. Student buy-in is high because they see the value of retrieval. Within the quizzes, I include questions from previous chapters and units to create spaced practice opportunities that are difficult for students to build into their own schedules. Students receive retrieval practice assignments both in-class and as homework nearly every day. To encourage spaced practice I usually give a weekly challenge grid, an idea I learned from Kate Jones (2018).

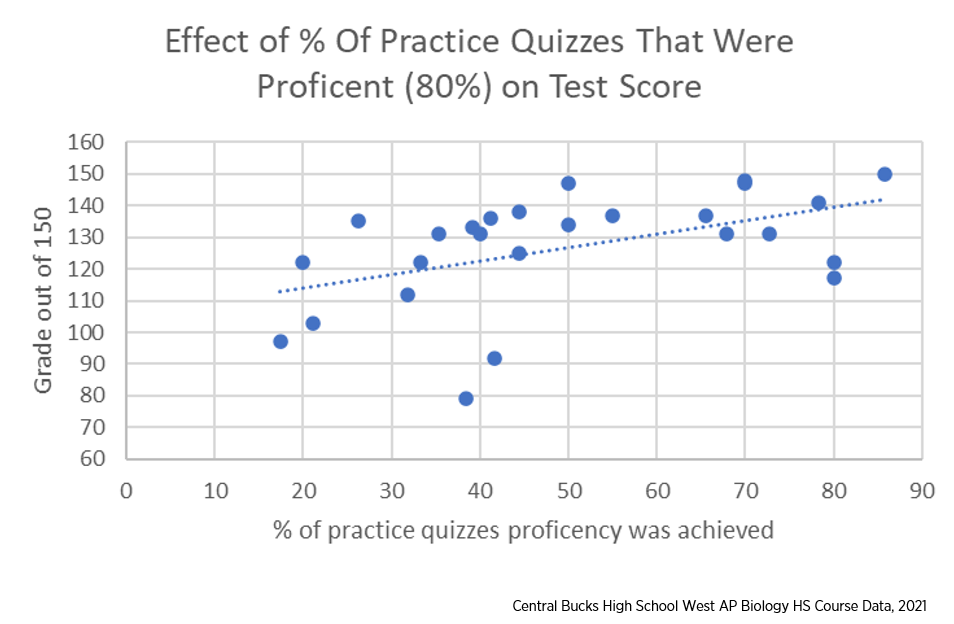

Let the Science Drive Your Classroom

We know students perceive classmates who do well in school as having innate talent (Hambrick et al., 2016). I dispel this myth with my students by sharing their own class data, attributing success to hard work rather than innate talent. Students who are doing well on assessments are also students who are doing necessary work outside of class. Additionally, just completing work isn’t enough. The practice that is being done needs to be high-quality. High quality means students are attempting practice initially without notes, reflecting on what was incorrect and then reattempting practice until they are regularly scoring 80-90% correct. I try to create graphs that speak to students. I devote class time for students to reflect on the data that they are seeing and how they can use that data to inform their practice and study strategies moving forward.

Moving from Earning to Learning

Teaching students about how their brains work and then developing lessons around retrieval, spaced practice, and metacognition shifts the burden of learning from the teacher to the learner in the most positive way possible. It wasn’t until after I began embracing cognitive science that I began to see that my grading practices were actually working against my classroom philosophy. If my goal for students is to learn the objectives that I post in my classroom every day then why would I discourage them from reassessing? Why would I limit the grade of a retake to 70%?

I believe teachers need to do everything in our power to motivate students to learn, not just comply, within the constraints of a traditional classroom. It is essential for students to see that devoting time to high-quality practice allows them to acquire knowledge and experience success both in school, higher education, and in their future careers.

With this new perspective based in cognitive science, I decided to reduce the number of graded assignments in my classroom. I developed extensive question banks so that I could give students the opportunity to reassess on formative assessments and use those reassessments as learning opportunities. When assignments are open ended, such as laboratory reports, I give feedback and devote time in class for students to respond to feedback and resubmit their work. I don’t place a grade on the task until students have responded to feedback. Here are some of the things my students have shared with me as a reflection at the end of our courses together:

“I loved having you as my teacher. Thank you for always being there for me when I needed help and believing in me. You really helped to boost my confidence in my test taking skills. You really made a big impact on my academic career. Thank you for an enjoyable semester. I will for sure come by and visit.”

“You were a great teacher and have taught me more than any other teacher so far. I can not thank you enough, as you have not only helped in the classroom but also outside the classroom. This class made me feel more confident in my schooling and I felt more prepared to learn in all of my other classes. I could not ask for my year to go any different, and thanks a lot for all your hard work. It does not go unnoticed.”

For me, teaching continues to be a work in progress. I still don’t do everything well, and some students still struggle in my class. But the story I tell myself about who I am as an educator has changed. I have a lot more control over what happens in my classroom than I ever realized. I know that small changes can have huge impacts.

Key Terms:

Information Processing: A model used to describe the stages of learning, stating that sensory information that is attended to is encoded, encoded information is stored in short term memory and some of the information in short term memory becomes stored in long term memory. Long term memories can be retrieved back into working memory to be used during cognitive tasks.

Working Memory: Memory that is limited in capacity and holds information temporarily while executing a cognitive task

Long-Term Memory: Unlimited memory that involves the storage of information over a long period of time (days, weeks, years)

Encoding: Taking sensory information and holding it in working memory

Spaced Practice: Also known as distributed practice, this is the intentional practice of retrieving information at regular intervals (days, weeks and months), this is in contrast to massed practice where information is retrieved during one long study session

Retrieval: The process of bringing information from long term memory back into working memory

Strategies You Can Try in Your Classroom

Challenge Grids by Kate Jones

Brain Book Buddy by Blake Harvard

Retrieval Guides by Patrice Bain and Pooja Agarwal

Brain Dump by Pooja K. Agarwal

Relevant Learning Scientists Podcasts:

Episode 2 - Retrieval Practice

Episode 4 - Spaced Practice

Learn More about Cognitive Science & Education

References:

Gonzalez, J., Smith, M., & Weinstein, Y. (2016). 6 powerful learning strategies you must share with students (No. 58). Cult of Pedagogy.

Hambrick, D. Z., Ullen, F., & Mosing, M. (2016). Is innate talent a myth? Scientific American.

Jones, K. (2018). Retrieval practice challenge grids for the classroom. Love to Teach: Research and Resources for Every Classroom.

Smelser, N. J., & Baltes, P. B. (eds.) (2001). International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences. Elsevier.

Learn how to use these strategies to increase your students’ learning and engagement.

About the Author

Alison teaches Human Anatomy and Physiology and Biology at Central Bucks High School West in Central Bucks School District in Doylestown, PA. She is a National Board Certified Teacher, the 2015 recipient of the Outstanding Educator Award from Stephenson University, a Distinguished Modern Classroom Educator and Modern Classroom Mentor. Alison has a passion for using evidence-based practice to improve student outcomes in her classroom. Follow her on Twitter at @alisonstoneCBSD.